This is a guest post from Diane Fiksel, Principal and Co-Founder, Eco-Nomics LLC and former Board Member of The Women’s Fund of Central Ohio. Diane attended the IDS Luncheon last month and offered to share the story of her visit to PUKAR in Mumbai. Thanks, Diane, for putting this post together for us!

In January 2017, I had the opportunity to visit an IDS-funded project located in Mumbai called PUKAR (which stands for Partners for Urban Knowledge, Action and Research.) While most IDS projects focus on rural development, PUKAR conducts cross-disciplinary research on issues related to the urban poor in Mumbai. What I found was a unique, innovative community-based participatory research model where the emphasis wasn’t on the findings of the research, but on the actual research process as catalyst for learning, advocacy, and transformation. Research serves as a means to engage young people in analyzing issues rooted in their everyday lives, thus creating a generation of critically thinking young people who are problem-solvers and agents of social change.

In January 2017, I had the opportunity to visit an IDS-funded project located in Mumbai called PUKAR (which stands for Partners for Urban Knowledge, Action and Research.) While most IDS projects focus on rural development, PUKAR conducts cross-disciplinary research on issues related to the urban poor in Mumbai. What I found was a unique, innovative community-based participatory research model where the emphasis wasn’t on the findings of the research, but on the actual research process as catalyst for learning, advocacy, and transformation. Research serves as a means to engage young people in analyzing issues rooted in their everyday lives, thus creating a generation of critically thinking young people who are problem-solvers and agents of social change.

Investigating why slum children drop out of school at an early age.

Investigating why slum children drop out of school at an early age.- Documenting the working conditions of women in small scale industries.

- Exploring how families restrict girls’ access to the internet, and the implications.

Then they communicate the results back to their communities, often in the form of artworks or visual aids, and they initiate a dialogue about opportunities for positive change.

Then they communicate the results back to their communities, often in the form of artworks or visual aids, and they initiate a dialogue about opportunities for positive change.

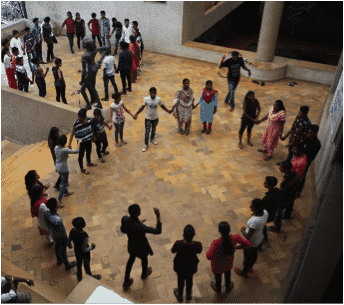

Many of the PUKAR researchers choose to study aspects of their family or community culture, such as their parents’ livelihoods. As they learn how to capture and analyze data about their subjects, this often leads to greater self-awareness and personal transformation. Documentation is an important part of their research methodology, and usually beginning with documentation of their own identity. As their work extends into the broader community, they learn about collaboration and teamwork with others.

Many of the PUKAR researchers choose to study aspects of their family or community culture, such as their parents’ livelihoods. As they learn how to capture and analyze data about their subjects, this often leads to greater self-awareness and personal transformation. Documentation is an important part of their research methodology, and usually beginning with documentation of their own identity. As their work extends into the broader community, they learn about collaboration and teamwork with others.

I believe that PUKAR’s community-based participatory research model could be replicated in U.S. cities such as Chicago. Rather than allowing youths to become alienated from their communities, such a program can empower them to be change agents. Taking a community-based grass-roots approach teaches youths to listen to all stakeholders, to respect tradition while recognizing the need for progress, and inspires them to mobilize new initiatives that make sense for their community.

Here’s the website if you would like more information: https://www.pukar.org.in/

Diane G. Fiksel

I believe that PUKAR’s community-based participatory research model could be replicated in U.S. cities such as Chicago. Rather than allowing youths to become alienated from their communities, such a program can empower them to be change agents. Taking a community-based grass-roots approach teaches youths to listen to all stakeholders, to respect tradition while recognizing the need for progress, and inspires them to mobilize new initiatives that make sense for their community.

Here’s the website if you would like more information: https://www.pukar.org.in/

Diane G. Fiksel